UEC Profile: Maven of Remote Sensing and Radar Retrievals

Published: 23 April 2019

A young scientist presses for improvements in radar retrievals of snowfall properties, cloud microphysics, and more

This is the fourth article in a series of 2019 profiles on members of the ARM User Executive Committee (UEC).

In early January 2009, German meteorology undergraduate Maximilian Maahn began a six-month semester abroad at the University Centre in Svalbard, Norway. During the winter months, this mountainous archipelago in the Arctic Ocean—just 650 miles from the North Pole—is pitch-dark 24 hours a day.

“I had to wait for a full moon to see where I was,” says Maahn.

He finally viewed the surrounding terrain two weeks after arriving: conical mountains streaked with snow, steep valleys, and cliffs butting against frozen-over ocean bays. Behind the student housing, a glacier doubled as a ski slope.

This frigidly exotic place “sparked my passion for polar regions,” says Maahn from his office in Boulder, Colorado.

He is a research scientist with the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES) at the University of Colorado, Boulder, which is affiliated with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Earth System Research Laboratory (ESRL).

A decade after his sojourn in Svalbard, where polar bears outnumber humans, Maahn is an energetic fixture in the Polar Observations and Processes team, part of ESRL’s Physical Sciences Division. He works on advanced modes of remote sensing, with a focus on radar observations and retrievals, as well as cloud and precipitation processes.

In models designed to predict Earth’s future climate, the biggest uncertainties relate to clouds and precipitation, says Maahn. “I study them with measurements, try to improve those measurements, and use the results to explain processes. With this understanding, you can improve models.”

Well ARMed

In pursuit of such work, Maahn cowrote a 2012 paper on a Micro Rain Radar processing scheme—his first as lead author—on how to improve the characterization of snowfall. With co-author and veteran radar expert Pavlos Kollias, he proposed an improved processing method especially suited for snow observations.

Two later papers—one on ice cloud observations (2015) and another on improved radar retrievals of cloud microphysics (2017)—used data from an entity that Maahn says “profoundly influenced my academic and professional life,” and which he first encountered as an undergraduate in Germany: the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Atmospheric Radiation Measurement user facility.

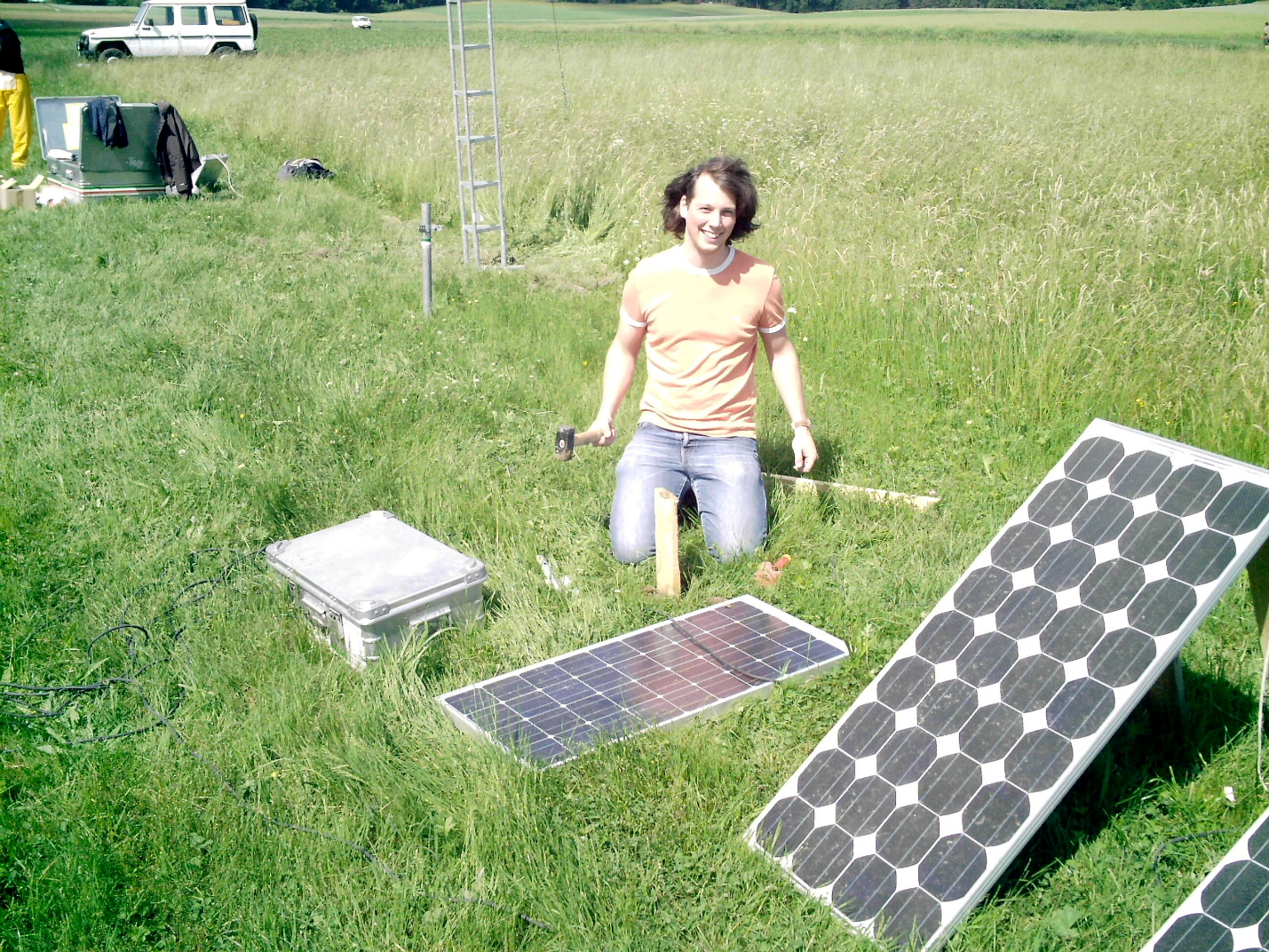

In 2007, while doing fieldwork with classmates at the University of Bonn, Maahn encountered scientists in Germany’s Black Forest during ARM’s Convective and Orographically-induced Precipitation Study (COPS), a field campaign designed to study precipitation from atmospheric uplift.

For a student contribution to COPS, he took up a job managing a precipitation counter—an important moment in his emerging identity as a scientist.

“This was the first time I got involved in measuring stuff,” says Maahn.

He went on to receive the German equivalent of a dual bachelor’s and master’s degree at the University of Bonn in 2010.

Later, as a first-year doctoral student at the University of Cologne in Germany (PhD, 2015), Maahn traveled to ARM’s Southern Great Plains atmospheric observatory. There he oversaw a German radiometer during the Midlatitude Continental Convective Clouds Experiment (MC3E), a 2011 ARM-NASA field campaign investigating convective processes.

“If it works out as it’s supposed to, MOSAiC has the potential (to generate) one of the most complete, exciting data sets for the next decade.” — Maahn

“If it works out as it’s supposed to, MOSAiC has the potential (to generate) one of the most complete, exciting data sets for the next decade,” says Maahn. “From a radar perspective, there is everything you can imagine. All the checkboxes are marked.”

Half of Maahn’s time goes to the Polar Observations and Processes group led by de Boer. The other half—just recently—goes to a project headed by arctic research colleague Amy Solomon that’s about “tapping into the modeling business to better understand the needs of modeling people,” says Maahn.

That’s another dream of his—combining modeling and observations into an integrated framework.

“A model has a thousand knobs you can turn,” says Maahn. “It’s hard to correlate all these knobs with the thing you can observe in the atmosphere. We need to connect these two worlds.”

Getting There

Not long ago, Maahn ran into his childhood nanny. “Oh,” he recalls her saying. “I always knew you would be a scientist!”

Early on, he had an affinity for math and physics—though not directly from his parents. Maahn’s father is a musician, and his mother runs a family business.

High school in Cologne was the end of a rigorous 13-year college-preparatory course of study. It was followed by a then-mandatory year of service, during which he supervised a group of disabled factory workers.

“It taught me a lot about life,” he says.

During that year, Maahn was unsure of what to pursue at university. He finally chose physics, but only if it was in an applied way.

“That was the motivation to study atmospheric science,” says Maahn. “I was afraid physics would be too far from reality. You have to have a relation to the subject you are studying. It’s not like quantum physics.”

Still, he says, “I was never the guy counting clouds or collecting cloud pictures or watching forecasts.”

Atmospheric microphysics was the draw, along with radar systems where insight comes from complex, mathematically intriguing spectra of data points that tilt in wave-like curves.

Moving to the University of Cologne for his PhD work, he joined the Integrated Remote Sensing group—“a perfect match” of personalities, “vibe,” and funding, says Maahn.

He worked with polar researcher, mentor, and dissertation advisor Ulrich Löhnert, who steered him to ARM’s ISDAC data.

During another trip to the United States, at an ARM meeting, Maahn heard de Boer say he would soon need a postdoctoral researcher in Boulder.

That same day, says Maahn, “I grabbed him and showed him my poster.”

His girlfriend (now wife) was persuaded to move to Colorado in 2016. All it took was researching what Boulder is like.

“We love to hike and go camping in the mountains,” says Maahn—though that lifestyle is just now being revived since the birth of their son two years ago.

While outdoors, he views the sky as more than just a subject for math and physics. “Luckily, I still see clouds.”

Keep up with the Atmospheric Observer

Updates on ARM news, events, and opportunities delivered to your inbox

ARM User Profile

ARM welcomes users from all institutions and nations. A free ARM user account is needed to access ARM data.