Osinachi Ajoku: Student of Clouds, Advocate for a Diverse Research Pipeline

Published: 25 May 2023

An early career scientist takes on a new role and a project to improve models of marine clouds

Editor’s note: This is the first article in the 2023–2024 series of profiles on members of the ARM User Executive Committee (UEC).

Howard University atmospheric scientist Osinachi Ajoku, one of five siblings, was born in Los Angeles, California. He grew to love numbers, to love science, and, in graduate school, to love the puzzle of clouds and aerosols.

His academic career at Howard, just 2 years old, has given him the chance to share what he has learned about the atmosphere, as well as the path that took him to the front of the classroom.

“Mentoring to me is a priority,” says Ajoku, an advocate for getting a diverse group of students into science and whose climate lab page blends aerosol science and mentoring. “You have to be the change you want to be.”

Along the way, as a PhD student, he came across a rich source of data on the marine clouds he was studying: the Atmospheric Radiation Measurement (ARM) user facility.

ARM, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science national scientific user facility, operates six atmospheric observatories in climate-critical regions of the world. After 31 years, the ARM Data Center houses more than 4 petabytes of data—equivalent to all the data in the Library of Congress times 200.

Among its voluminous measurements, ARM has collected data on marine cloud processes in the subequatorial South Atlantic Ocean, lately the scene of Ajoku’s top research interest.

“In order to understand the intensity of precipitation,” he says, “it’s important to understand what’s happening in the clouds.”

Useful in the UEC

Circumstances have brought Ajoku back to ARM in a unique way. He is one of the newest members of ARM’s User Executive Committee (UEC). Currently consisting of 14 scientists from national laboratories and universities, this elected group represents the ARM user community in interactions with ARM management.

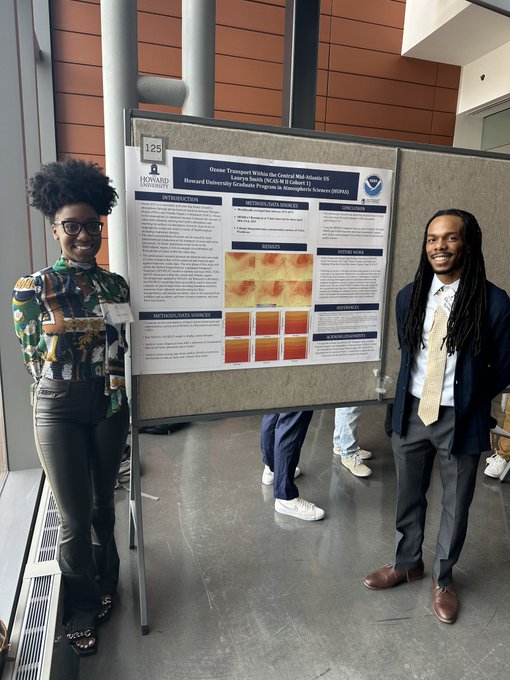

Within the last few months, Ajoku took the reins of the UEC’s subgroup on undergraduate engagement with a focus on diversity.

“It’s all about the research pipeline and strengthening that,” says Ajoku. “That means going back further and training undergraduates earlier about what graduate studies are like.”

“It’s refreshing―it’s indescribable―to see someone else’s success.”

Osinachi Ajoku, Howard University

Getting exposure to the rigors of graduate school, he adds, “starts with students as freshmen. More people that look like me: That was a big motivation.”

It will help that in 2022 Ajoku received a two-year grant from DOE’s Research Development and Partnership Pilot to accelerate diversity among climate researchers.

He calls mentoring students “the best part of my job. It’s refreshing―it’s indescribable―to see someone else’s success.”

Smoke and Clouds

Ajoku has other reasons to have ARM on his mind.

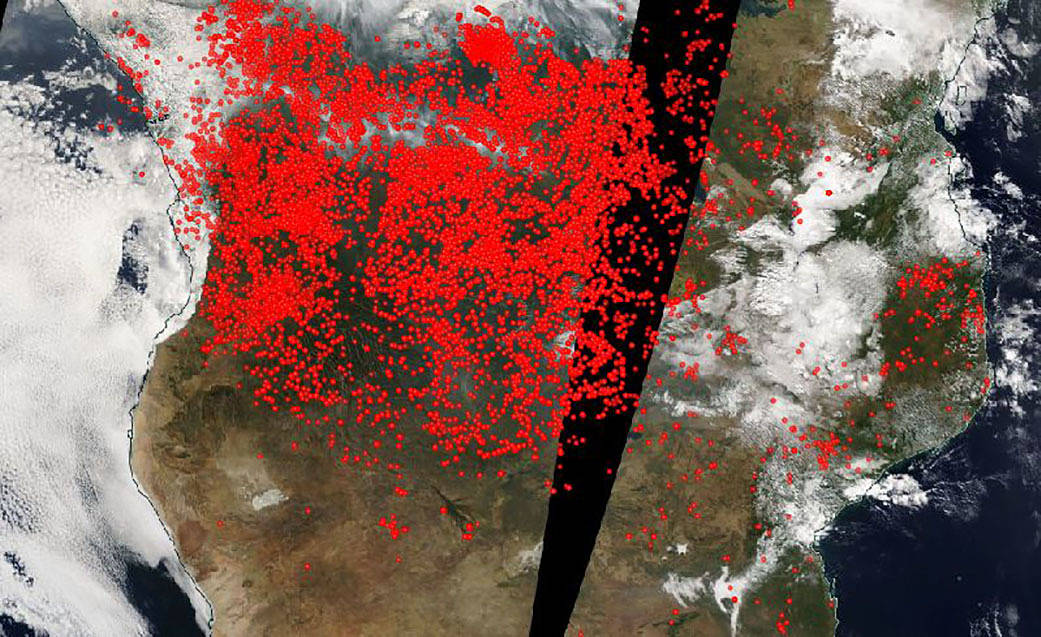

Measurements from a 2016–2017 ARM field campaign called Layered Atlantic Smoke Interactions with Clouds (LASIC) are at the heart of a major project of his on modeling marine cloud impacts of biomass burning in sub-Saharan Africa.

DOE’s Atmospheric System Research (ASR), a sister program of ARM’s, is funding Ajoku’s work as principal investigator.

Joined by co-principal investigator Joseph Wilkins of Howard University, Ajoku will investigate how smoke affects cloud regimes in the South Atlantic Ocean―how they form and how they transition from one type to the next.

“In the last three years, fires have gained a lot of headway in the media,” says Ajoku. “In Nigeria, I know fires are an every-year occurrence, and smoke pollution is a daily occurrence. But less is known about how smoke affects low marine clouds.”

Marine stratocumulus and cumulus clouds are more numerous than any other type, he says, and an ocean setting off the west coast of Africa “is the perfect testbed” for studying smoke-marine cloud interactions.

Ajoku and Wilkins are combing through satellite observations of stratocumulus clouds, looking for days with polluted and clean conditions.

“From these satellite snapshots,” says Ajoku, “we can start looking at the LASIC data, which are easily available.”

First, Seeing a Red Sun

Ajoku was 5 years old when he traveled with his parents to their native Nigeria. He remembers seeing a giant midday sun, obscured in a haze of smoke, hanging in the sky like a blurry red disk.

“Science was a foreign language then,” says Ajoku, the son of a businessman and a nurse. “But what stood out were the images. Every time I went to Nigeria, I could not see the sun.”

Why that was true, he adds, “I never understood until I got to graduate school.”

Other images of atmospheric phenomena turn up as memories for Ajoku, whose lifelong facility for numbers has also given him a knack for remembering exact dates. At age 9, Christmas Day 1998 “was the first day of my life I saw hail falling on the ground.”

He ran to his mother and said, “Hey, rocks are falling out of the sky!”

In 2003, at Susan Miller Dorsey High School in south Los Angeles, Ajoku joined a program that brought practicing architectural engineers into classrooms. He helped build the blueprints for a rail line that opened 10 years later between the University of Southern California and Santa Monica.

It was, he recalls, “an amazing feeling.”

While still in high school, Ajoku also interned with the Fox Emerging Professionals Mentor Program, which offered clinical work, a free lunch, and a way “to get inner city residents out of the neighborhood,” he says.

For a time, Ajoku helped engineers work soundboards for voice actors from the television series “The Simpsons.”

Steering Into Science

At first, Ajoku studied biomedical engineering at California State University, Dominguez Hills, “but I saw early on I was not built for engineering.”

By February 2009, after a swerve into a B.A. program in geography, he was seized with the idea of getting a doctorate in hard science. Earth science, and its path to a B.S., rose as a choice “in order to be a better (PhD) candidate,” says Ajoku.

It was the same year he became a vegan, a lifestyle choice that led him deeply into the science of nutrition, “looking at plants in nature,” and the work of German naturopath Arnold Ehret.

After graduating with his B.S. in earth science in 2011, Ajoku took a year off to work at Dominguez Hills with earth scientist Ashish Sinha, whose paleoclimate work involved studying stalagmite samples from caves in India.

In 2023, Ajoku co-authored a paper on related work about paleoclimate changes in the Pacific Northwest.

“I am glad I caught some of that enthusiasm,” he says of the experience with Sinha―an interlude that also provided further lessons on surviving doctoral studies.

His introduction to aerosols and clouds came at the University of California, Riverside (M.S., geosciences, 2014) during work on forcing agents in the tropics with climate change researcher Robert Allen.

“That’s my guy. He was there from Day One,” says Ajoku, who before his time at Riverside “had never heard of aerosols before, even in chemistry.”

On to a PhD

Starting from scratch, Ajoku quickly seized on the idea of aerosols as “the most important topic on the planet,” he says. “Every single cloud you see is composed of aerosols.”

Then came two big boosts of funding for an advanced degree: three years from a National Science Foundation graduate research fellowship and two from the University of California, San Diego (UCSD).

Ajoku began his PhD studies at UCSD’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography with a July 2014 graduate division program on the dynamics of getting a doctorate―a fire hose of information, he remembers. “It was overwhelming. I’ll be totally honest.”

At Dominguez Hills, he was one of a dozen undergraduates in his major. At Riverside, there were 25 students in the master’s program. At Scripps, there were close to 300 graduate students.

But Ajoku got two mentors he leaned on throughout his PhD work: oceanographer Art Miller and climate scientist Joel Norris. Both were advisors for his dissertation, a warmup for the ASR project: an investigation of smoke aerosols on West African climate dynamics.

Along the way, he was among representatives from Scripps who attended three successive Conferences of the Parties―in 2016, 2017, and 2018. “Parties” is a reference to those that signed the 1992 Kyoto Protocol to limit and reduce the production of greenhouse gases.

Ajoku received his PhD in 2020, becoming the first person in his family to earn a doctorate.

“More people that look like me are getting higher degrees,” says Ajoku of why he stood for election to the UEC. “That was a big motivation for me becoming part of the process.”

Keep up with the Atmospheric Observer

Updates on ARM news, events, and opportunities delivered to your inbox

ARM User Profile

ARM welcomes users from all institutions and nations. A free ARM user account is needed to access ARM data.